What is a Tiger Bass, you ask?

Kevin VanDam Foundation may have put Oklahoma on a roll toward something big

Several times this week I brought up the subject of Tiger Bass with other anglers.

Several times I heard a similar response.

“What the heck is a Tiger Bass?”

There are anglers, and then there are bass anglers. If you are a bass angler you probably have heard of tiger bass over a beer, or possibly even read something about them. If you’re a fly-fisher, a noodler, or a crappie nut, Tiger Bass likely is not in your vocabulary.

The conversations drove home to me the position our state agencies are in when it comes to wildlife management and how some decisions can become, for lack of a better term, political. Typically, the reaction among the otherwise interested is something along the lines of, “why are they spending money on that when they could be doing something better?”

“Better,” being anything closer to what you personally care about.

I love all kinds of fish and fishing—although I confess a preference for clear streams and native smallmouth bass on a fly rod—but what’s happening at Grand Lake is fascinating and could mean bigger things for our state.

The Tiger Bass program is not a draw on fishing license dollars, quite the opposite. It is entirely funded by private donations. In the long run, it could benefit all anglers with increased interest in Oklahoma’s bass, which means tourism dollars and more conservation dollars from licenses and gear purchased.

What’s a Tiger Bass?

So, what is a Tiger Bass and why should anyone care?

I first heard about them three years ago when I interviewed Northeast Region Fisheries Supervisor Josh Johnston about a different project on Grand. That one involves pure Florida-strain largemouth bass. He had initially considered Tiger Bass but couldn’t get the support to make it happen.

Tiger Bass is a registered trademark name (that’s why I’m capitalizing the name) of a hybrid Florida bass/northern bass fish created at the American Sport Fish Hatchery in Montgomery, Ala.

The hatchery claims they are of purer genetic makeup than other F-1 (first genetic hybrid) Florida-northern mixes. The fish are aggressive as northern feeders and have the potential to grow up to 2 pounds per year in ideal conditions, they say.

The Wildlife Department scored a great price on their shipment this month of 93,000 fish for $40,000. Support this time kicked off with a private donation at the Major League Fishing Redcrest Championship. The Kevin VanDam Foundation kicked in $5,000 and saw an immediate match from the Oklahoma Wildlife Conservation Foundation. Others chipped in and soon the $40,000 was ready to spend.

A matter of latitude

Three years back, Johnston told me about another northern lake, Smith Mountain in West Virginia, where Tiger Bass seemed to be showing enhanced trophy potential. That’s what had piqued his interest.

As a matter of latitudes, Smith Mountain is at about N37.5° and Grand is at N36.5°

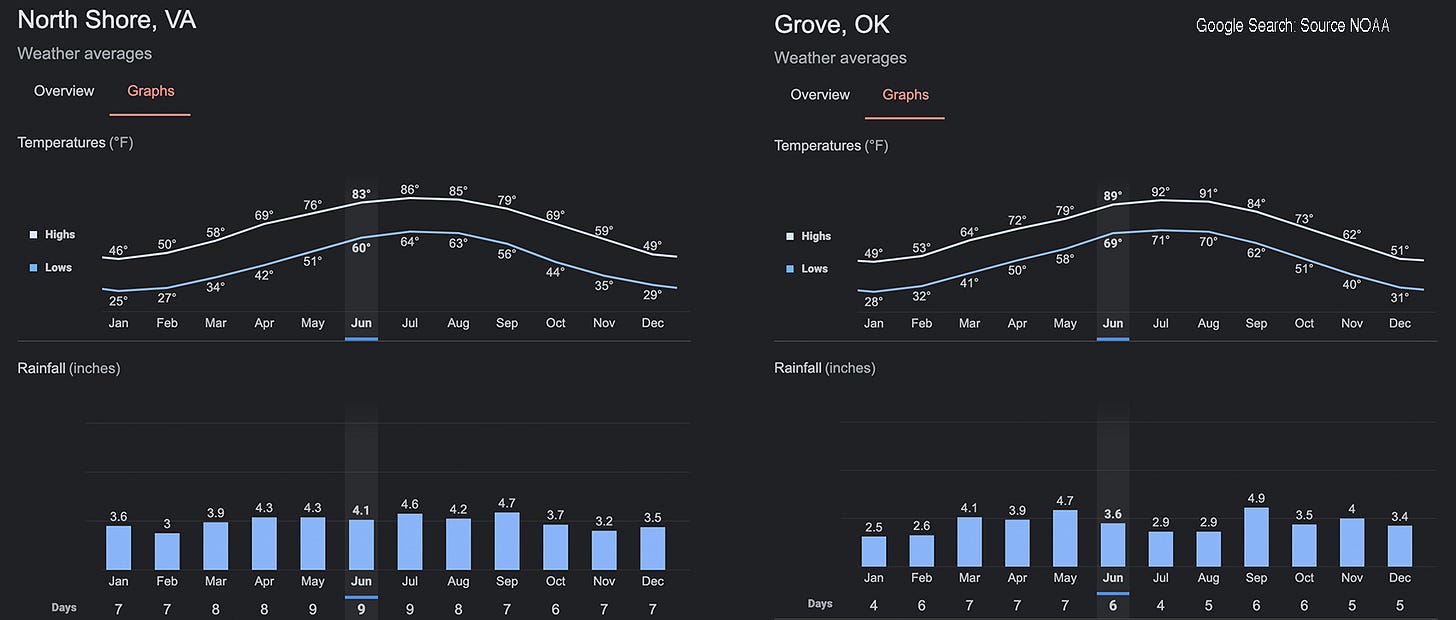

Weather at the town of North Shore at Smith Mountain runs on average a smidge cooler than at Grove, on Grand Lake, in the hottest and coldest months of the year. About six years into their program now, Virginia biologists see some promise and now stock Tiger Bass in five different lakes.

“We’re stocking at alternate levels to see what kind of response we get for the most cost-effective approach,” said Mike Bednarski, chief of fisheries with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources.

“We are seeing positive results,” he said. “We are seeing larger bass in sampling studies and in tournaments that we can attribute to Tiger Bass. At this point, it has been surprisingly positive and it’s certainly something we’re continuing to look at if it can be cost-effective and produce larger bass.”

Bednarski didn’t have sizes to cite off the top of his head. He could only say the fish are larger than they’ve seen in the past, but they’re obviously not putting on 2 pounds a year.

Floridas and Tigers in Grand

In the 1980s the Wildlife Department put thousands of pure Florida strain bass into our lakes. Only the bass in the more southern parts of the state survived—and went on to produce state records and to justify the state’s continued Florida-bass stocking program.

In northern lakes—with a few exceptions—the fry disappeared.

As part of the state’s continuing hatchery program for pure Florida-strain bass, a batch of anywhere from a few dozen to a few hundred extra mature brood stock exists each year. In years past those highly desired Florida brooders were distributed to various lakes around the state. They will be again in the future, but for the past three years all of those brooders went into one particular location at Grand.

Johnston and his crew will monitor those stocks and watch for their DNA, which they hope will turn up as homemade F-1s (and other generations) in Grand Lake. Johnston calls these fish the “grow out” program fish.

It was pure chance that in the third year of his three-year project with the Florida brooders that the Tiger Bass opportunity arose.

For the biologist, it’s a chance to double up on opportunities to make trophy-class fish for anglers—and to study the genetics and growth rates of these different fish, all in a forage-rich environment at this northern latitude.

“There are things we don’t know about these fish,” Johnston said. “What we do know about Tiger Bass in a 50-50 cross is that you get both parent genetics. So, you’re going to get the thermal tolerance of a northern strain largemouth bass and the growth potential of a Florida bass. The thing that we don’t know is, is that growth potential enough to outweigh the fact that those genetics are not supposed to be in this climate?? Just because they can get big doesn’t mean they will when you put them in a climate those genetics aren’t supposed to be in.”

Fingerlings on the prowl

At two fingerlings per acre in 46,000-acre Grand Lake, 93,000 little 2-inch fish doesn’t seem like much and, as Johnston put it, “it isn’t.”

The strategy behind stocking these 2-inch fingerlings at the rate of about 30,000 each in the upper ends of Horse, Honey, and Duck creeks now is that thousands of other fingerlings are present. Native hatched bass fingerlings and other young fish—likely a bit smaller—also are in the water at this time and keeping predators busy.

That gives the Tigers a leg-up for survival this spring, he said.

Concentrating the fish in these creeks also gives the biologists a chance to find them next year. Young bass don’t move far, Johnston said, so the odds of finding these fish again and collecting DNA samples for years to come are enhanced.

Johnston’s aim is to find funding for Tiger Bass stocking every year for the next 10 years. Regardless, biologists will pull DNA samples and perhaps in the future tournament directors, too, will be asked to pull fin clips off any bass that is, say, over 8 pounds.

Anglers will have their part to play in this, and that means sharing information about the fishing, and keeping and eating smaller bass.

Grand has plenty of bass. The Florida-strain-related stockings are about creating trophy potential, not more fish. So, when it comes to bass the catch-and-release theme should apply only to the largest specimens. Keep the smaller ones and fry ‘em up. Hopefully, in a few years, there will be more and more of those true trophies to go around.