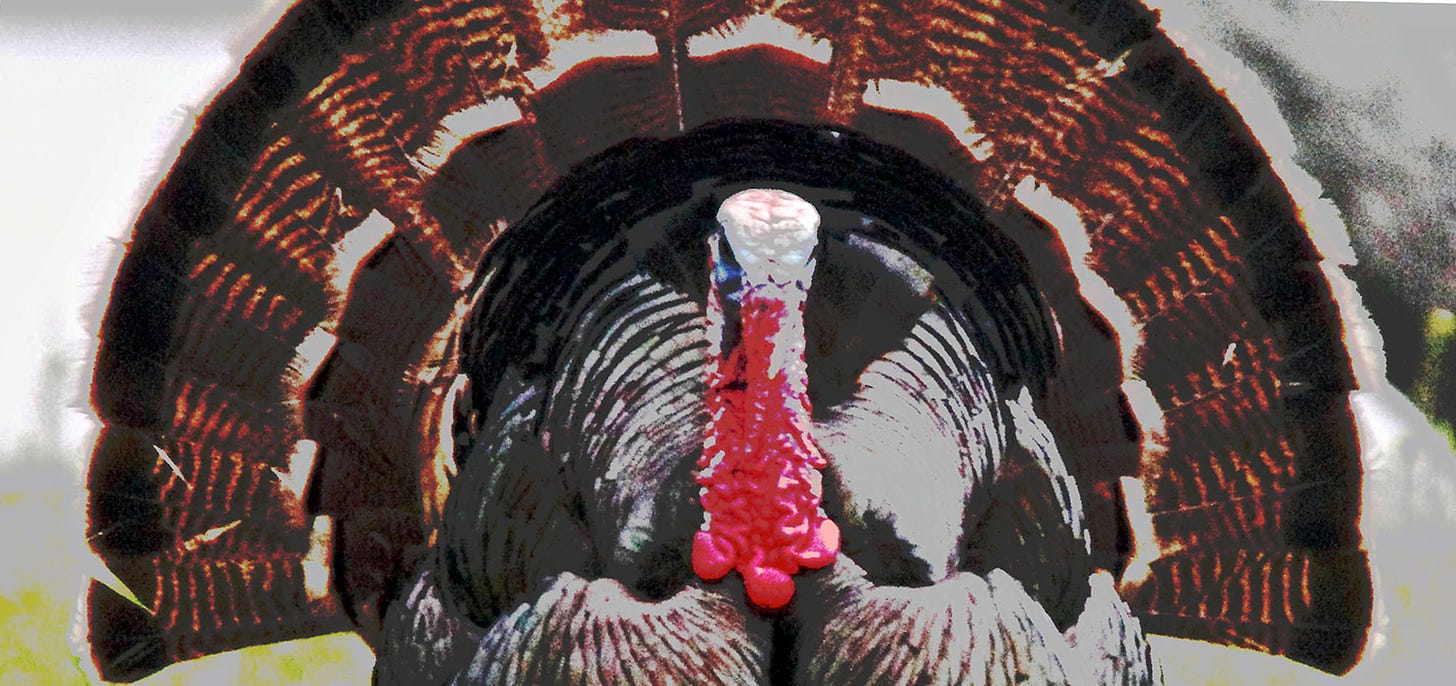

Turkey worry multiplies, population declines

Oklahoma's turkeys can spring back but the road ahead looks challenging

The late Sam Powell took me on a drive around the countryside upon my arrival to this state the fall of 2008. I was about to take the longtime Tulsa World outdoors writer’s spot and this was my new employee tour.

My recollection is I noticed the change in landscape and the presence of pines as we rolled toward Sequoyah State Park and talk immediately turned from crappie and bass to the fact that I really must hunt eastern longbeards in Southeast Oklahoma because it was a turkey hunting experience like none other in the state.

“But the population is down so I would wait another year or two for them to come back,” he said, and then I remember he hesitated as he had a little debate with himself about whether it would come back and whether I should just go now before it got even worse. We talked a little about weather and the volatility of populations among most ground-nesting birds.

In the end he decided the best advice was to wait and see about the populations. I had it set it in my mind that it sounded like a hard hunt anyway and I didn’t know anything about turkey hunting at the time so I set a goal to hunt those southeast pines in three or four years.

A year or two later the Special Southeast Zone was created with the season cut by two weeks and a 1-tom limit created for that nine-county area.

My 12th turkey season approaches and I still haven’t hunted southeast Oklahoma. Now I’m worrying about the rest of the state, too.

None of this should dissuade people from hunting this spring. There are still 15,000 to 20,000 birds out there waiting for someone to make all the right moves. But there are plenty of cues that should concern turkey hunters with an eye on the future.

I’ve seen the trend since I arrived in 2008. Turkey hunters still have a maximum of four turkeys they can take in a year, but the one-turkey limit for fall no longer includes counties that allow any-sex harvest. It is a one-tom limit where it is open, and fewer counties are open to fall hunting. Until last year we had a spring turkey zone map with most counties west of I-35 marked with a two-tom limit for spring season. Every county, except for the nine in the southeast region, is a one-tom county now. In the southeast it’s one tom from that entire region.

Southeast Oklahoma has settled into a new less-is-normal and my writings about the Southwest’s Rio Grande subspecies have evolved from stories about a tough, drought-tolerant species to a new lament about birds that just can’t seem to catch a break with the weather.

Eastern wild turkey project coordinator Eric Suttles with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation said turkeys there actually had one of their better nesting seasons of the decade in 2020 and the season to come should be on par with last year.

“We’re going to be OK,” he said. “Just kind of normal.”

Between 2000 and 2010 Oklahoma’s spring turkey harvests hit lows around 30,000 birds and highs over 40,000. Since then, the big years hit highs in the 26,000 range and lows around 18,000. Decade over decade, that’s about a 40 percent decline. Ouch.

We’re back to harvest levels of the late 1990s, but I’ll venture a guess that hunting effort now is much higher than it was back then and our habitat, generally, is in tougher shape. That means a recovery to those 2006 and 2009 years with more than 40,000 birds taken will be a tough row to hoe. We’ll need a string of perfect weather years but weather the past decade seems to trend more toward the volatile.

“Tumultuous,” is how Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Southwest Region supervisor Rod Smith described weather that hit the southern region birds.

They have faced repeated drought years pock marked with gully-washers at the most vulnerable points in the nesting season, he said.

“We had those hard rains and then, boom, right back into drought again,” he said.

Statewide, this season probably will be remembered as “spotty,” he said. Some areas are in pretty good shape and others simply are not. Most of the northern and eastern portions of the state probably won’t be much different in 2021 than they were in 2020, he said.

“As a real general statement, the farther south you go the worse it is,” he said. “The northern areas in west are down too, but not to the magnitude of the southwest.”

July counts of poults showed reproduction on par with recent years in most of the state, except the southwest, he said. The winter counts are down in some areas, but that may be a reflection of the February ice storms and snow during the count. It’s hard for people to count birds when they’re stuck in their own driveways.

Smith is the guy I used to talk to about Rios and how well they handled the drought compared to eastern or mixed eastern/Rio birds. They still do, but every species has its limits before things start to add up.

In our annual call this spring he told me things in the southwest portion of the state are bad enough that a few guides have called off their seasons—not all, but a few. He acknowledged there are internal discussions at the Wildlife Department about more changes to turkey seasons. And then he uttered those words that have filled every quail hunter with dread the past two decades.

“We have a research project cranking up and hopefully that will answer some questions,” Smith said.

That tells me things are serious indeed but I’ll still be out there next month. The next two weeks will tell me how my “spots” have fared, but I might just be going with my camera instead of my shotgun.