Trashed fish: Science for gar, buffalo targeted by bowfishing long overdue

Social media salvo a hint that more problems are brewing for bowfishing's image

The first long-nosed gar I saw up close and personal was drying in the sun, gasping for air, lying on a stinking bank next to some of its brethren that had rotted there for days.

“You get one of those damned things just throw it on the bank!” advised old-timer standing a few feet away. “They eat the good fish.”

Differences in attitudes and opinions run wide about so-called rough fish, trash fish, or non-game fish such as gar, carp and buffalo. Some people see them as little more than nuisance fish. Some assume they are non-native invasive fish. Some just see fun targets.

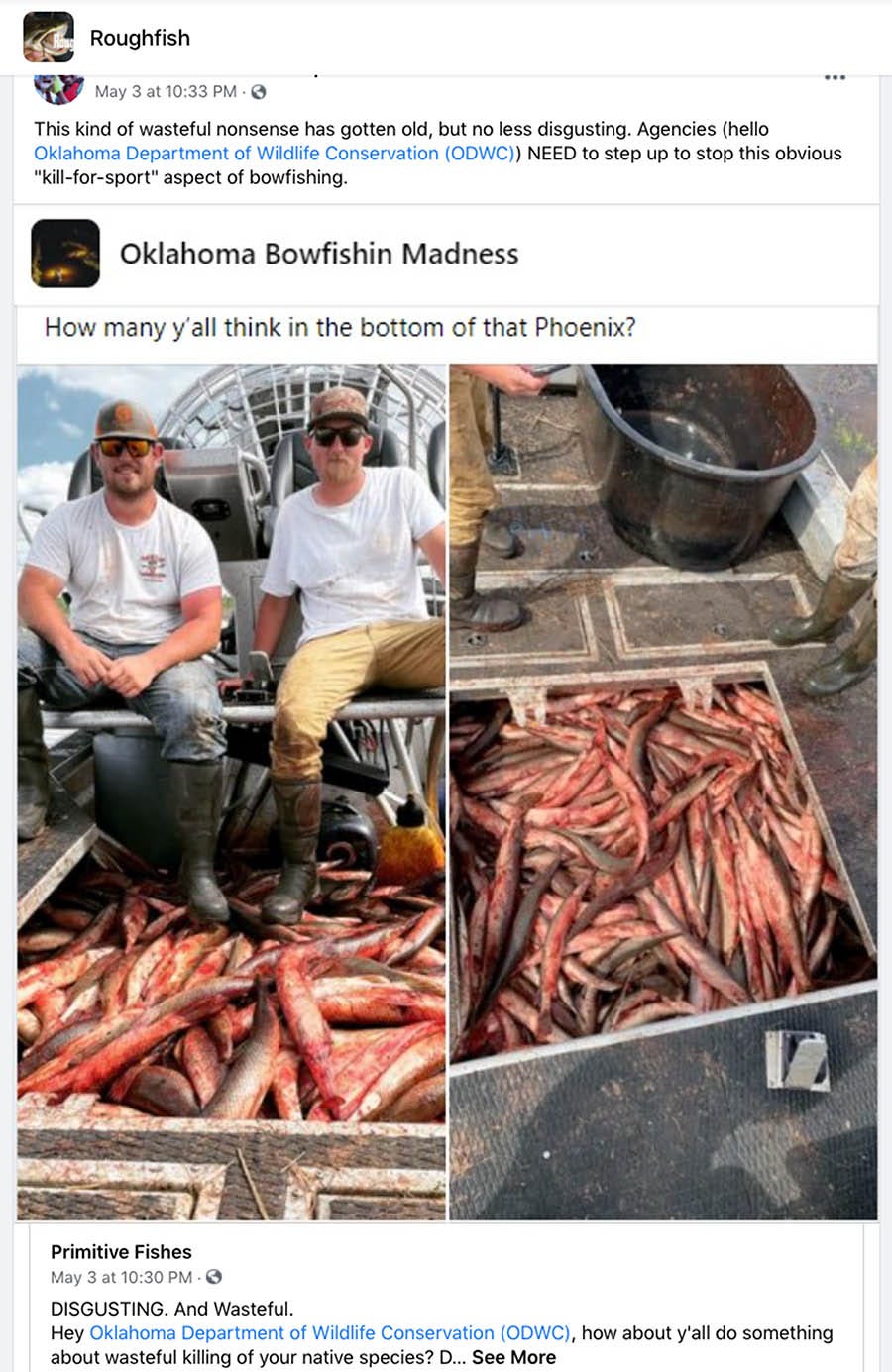

This train of thought springs to mind with contentious Facebook postings this month that started with an early post on the Oklahoma Bowfishin Madness Facebook group. Some bowfishers on an airboat sat with their feet resting atop a hold filled nearly to the brim with gar.

The bowfishers bragged in the post, “How may y’all think in the bottom of that Phoenix?”

It was followed by another post with a video of the guys tossing the fish overboard, counting them off and yelling a sort of tired yet jubilant “wo-hoo!” as the total passed 1,000.

The post inspired a different kind of Facebook enthusiasm among people who practice catch-and-release or eat-what-you-catch fishing of species like gar and carp on the Roughfish group.

People who follow the science-based Primitive Fishes group shared negative impressions as well.

“DISGUSTING. And Wasteful. Hey Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation, how about y’all do something about wasteful killing of your native species?...”

That was the start to a string of comments that grew less constructive but effectively related negative viewpoints aplenty.

Somewhere along the line some bowfishers defended the massive harvest by saying it was legal so everyone could just stick their viewpoints in a muddy hole somewhere until someone makes it illegal.

In the communications trade we recognize that kind of counterpoint as a politically foolish retort that simply begs someone who is already angry to pass a law—maybe several laws.

I’ve arrowed more than a few fish myself and done videos and stories about the sport. It is challenging, fun and exciting.

I’ve also caught (and released) buffalo and other rough fish on a fly rod and I want to do more of that. It too is challenging, fun and exciting.

Bowfishing combines bowhunting with fishing. It also mixes both ancient roots and new-fangled gadgetry. What combinations could be better?

Its popularity grows nationwide annually and it is almost a way of life for folks who invest tons of time and money to prowl the waters at night. It has given rise to another form of guided outdoor trip in Oklahoma, as well as large-scale tournaments with cash payouts and prizes. It is a healthy family activity and a beneficial economic engine. In states with invasive carp it is a great help in species management as well.

But as bowfishing grows so does its image problems, many of which are needless due to a few idiots who leave piles of rotting fish near boat docks or dump them into public park garbage cans or dumpsters.

Posts of videos and photos like the ones of the 1,000 dead gars don’t help with the image. If those guys had 1,000 dead invasive carp the reaction might have been different. If they had a mess of fish for a fish fry for hungry people it might have been different. If there was a biological base of knowledge and science-based regulation on the books that allowed unlimited harvest, it might have been different.

It’s not illegal, but it’s not exactly addressed. But in this case it didn’t even appear their disposal method was ethical. A majority of those fish were destined to float if the bellies and swim bladders weren’t cut. It didn’t appear that they were.

Those fish likely were found concentrated in shallow water while spawning. Maybe gars are extremely plentiful where those bowfishers hunted and, in the grand scheme of things, the biological impact was minimal. Public reaction to the images speaks for itself.

For its part, the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Department does seem to be paying attention and recognize its shortcomings.

The department proposed a new rule for this year that would have required bowfishers to keep all fish they arrowed until they stopped fishing for the day. Sharp public reaction to the idea cut it short—mostly for practical reasons raised by bowfishers who know the most about their sport. Dialogue on those kinds of ideas needs to continue, however.

The Wildlife Commission did amend existing rules to prohibit the disposal of fish remains within 100 yards of any boat ramp or swimming area this year, a change likely initiated at least in part due to bowfishing waste.

And at least one senior biologist has been looking closely into the issue.

Jason Schooley, a senior fisheries biologist with the Wildlife Department, co-authored a paper with Dennis L. Scarnecchia of the University of Idaho Department of Fish and Wildlife Sciences. It’s titled, Bowfishing in the United States: History, Status, Ecological Impact, and a Need for Management.

As the title states, the paper looks at the long history of bowfishing, the relatively recent growth of the activity in numbers of participants and technology, and it provides some detailed and important background for agencies new to the issue.

The long and short of the paper is that is describes how bowfishing is an expanding form of fish harvest that has vastly outpaced any study or oversight of how these fisheries should be monitored or managed for the health of the fish and long-term viability of the sport.

How did we get here? Well, who would care about a trash fish, a rough fish, a fish that we’ve grown up thinking we should toss on the bank because it “eats the good fish” or eats the eggs of the game fish we prefer? Where would the money come from to support that kind of research, management and oversight?

But it’s past time to address the subject. Recognition that we are making sporting use of native fishes for consumptive use can’t be ignored because someone came up with the term “trash fish.”

Bowfishing groups have posted articles and ideas about ethics in bowfishing and proper fish disposal. But they can expect that as the sport continues to grow the conflicts will as well.

Oklahoma’s bowfishers will need to step to the forefront of the debate and work with the Wildlife Department if they don’t want to be bowled over by a majority group spurred on by growing negative views and social media conflicts.

I am not a bowfisher. My first real introduction to bowfishing was when I walked up to a site on the Deep Fork River where I did monitoring with the Blue Thumb water quality education program. Apparently a few days before, someone had gone bowfishing for gar. They have left dozens of huge fish decaying on the banks. I see this as needless death and a stinky, gross situation for someone trying to do something good for the river.