Do you know this bass from that bass?

Usually it's clear enough, but hybrids can throw a kink into fish identification

How about a little drill on “how well do you know your fish species” today?

This comes courtesy of a mention on Facebook of the state’s record spotted bass not being a spotted bass about a month back, while I was in a tournament-related spotted bass ID question of my own.

It also follows a severe case of TBPB (Temperate Bass Photo Bewilderment) I endured during an August quest to catch a danged hybrid striped bass—and accurately identify it.

I promise, no lead-belly tournament fish jokes this weekend. We’ve seen enough of the Jake Runyan and Chase Cominsky debacle. You know, the Wisconsin walleye tourney anglers who stuffed lead weights and fillets into their fish last week. No Cominsky-Runyan methodology here.

I know I’m not alone in fish ID challenges, at times. It’s not always cut-and-dried, so I thought it might help to share a few examples of how even experienced hands can get into debates—save a fin clip and a DNA test.

Hope you enjoy the photos.

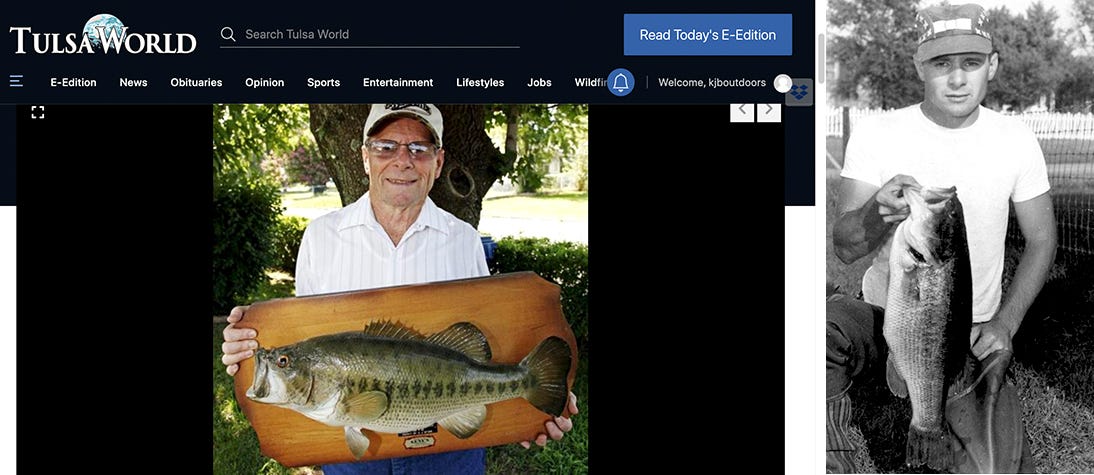

The spotted bass record question struck a chord because I wrote a story about that longest-standing record for the Tulsa World back in 2010, when Joe “OJ” Stone was 80 years old and the 1958 record of 8 pounds, 2 ounces crossed 52 years. It was a very short gee-whiz kind of “bright” for the sports page.

Sure enough, after taking a look at the photo with that story now that I’ve fished the Lower 48 for 14 years and hooked plenty of spots, I saw a guy holding a mount of a largemouth bass. Back then, I’m sure I wasn’t even aware of what made a spot a spot.

To check my vision, I ran it past biologist Josh Johnston, who is the northeast region fisheries supervisor with the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation. He agreed and acknowledged he likely was treading on dangerous ground. Most biologists would agree on that largemouth ID, he said.

No one can go back to 1958 to know what was the thinking, but the record was certified at that time and that’s that. Overturning the standing record now, after 64 years, seems like a cruel thing to do to the record holder. It’s just… too late.

It does seem like it at least deserves an asterisk to acknowledge the error and perhaps a second line for confirmed new spotted bass records that more accurately reflect the status of the species in Oklahoma.

Our state-records fish program has not been terribly robust since the lake records program dried up a few years back. The state’s website lists the top records only. No such thing as a second place here, but the department does list the Top 20 largemouths.

Possible records are one good reason to know fish IDs. More importantly for the average angler, the regulations place no limit on the number of spotted basses a person can keep. The limit on largemouth and smallmouth is six. That’s a pretty big deal.

During the summer’s 15-species fly-fishing challenge my brother rick needed a spot for his tally. We each caught nice spots as we apparently found a school of them on the Arkansas River downstream from Keystone Dam. The judges thought something looked “off” about the fish, however, and they went with “mean mouth.”

Looking at the same photos given to judges, Johnston replied by email, “the ones in your photos are all spotted bass in my book... interested in what caused folks to call them “mean mouths”.

Mean mouths are a natural hybridization that occurs between smallmouths and spots that closely inhabit the same areas and likely compete over spawning areas or establish nests and spawn near each other, he said. It happens, but it’s not common where the fish aren’t competing for limited spawning areas, he said.

Another part of the ID game is considering what swims the waters you’re fishing and what lives there or has been stocked, and when. Spots and smallmouths aren’t exactly crowded together in the upper Arkansas River so crosses should be exceedingly rare, if any. To hit a school of them in a pool downstream of Keystone dam is unlikely.

If I had to choose a starting point for my TBPB, Temperate Bass Photo Bewilderment, it started with the “yellow bass” I thought was a hybrid striped bass.

Knowing the temperate bass, meaning white bass (or sand bass), striped bass, and the white bass-striped bass hybrids stocked by the Wildlife Department is important. The limits are different for each species, and it can be tricky to know a hybrid from a white bass when the fish are 16 inches long or less.

A couple of others to throw in the mix, in the 8 inches or less category, are yellow bass and the invasive white perch.

Our team needed a hybrid striped bass and my brother, Rick, and I hit the Arkansas several times trying to catch one. I thought we had it done early in the process, but my “hybrid” was called a yellow bass because of broken lines in the body near the anal fin. Debate on the ID ensued and another view was that it was simply a sand bass.

I went with the yellow bass ID and claimed it as our team’s “wild card,” so it was not a total loss, tournament-wise.

Johnston eyed the photos and said, “I can’t see yellow bass in this fish. Interestingly, I would lean more toward hybrid striped bass.”

Good lord: A tournament judge thinks it’s a yellow bass, one thinks is a sand bass, another expert thinks it’s a hybrid of a sand bass (but not with a striper), and the state biologist looks at it and leans more toward hybrid striped bass.

No hard feelings about the tourney IDs, by the way. Part of the game is the fun of learning and challenging your ID skills. Judges have to make calls based on mobile phone pics on Facebook and you just go with what’s decided. Those are the rules and that’s that.

Hybrids can be tough, Johnston said. Generally, people look for broken lines and/or the number of lateral lines that clearly reach the tail, a bump on the head vs a smooth line, the body shape, or the hybrid and striped bass having two tooth patches instead of just one on a sand bass. The catch is that no single ID factor provides 100% surety. Only the clip of a fin and DNA can do that—or a combination of ID factors that convinces the officials.

As a cross between a striped bass and a white bass, some individual fish might show attributes more of the female in the breeding than the male, just like human children who might look more like their mom while siblings look more like dad, he said.

Several Oklahoma lakes and tail-waters contain both sand bass and hybrids, or striped bass as well, so when it comes to pleasing the game warden anglers should understand the differences and do their level best on IDs.

White perch and yellow bass IDs should be easy, Johnston said. The dorsal fins, with a spiny front and softer rays in the back, are connected. In the temperate bass, they are not.

“So if you manually erect the spiny dorsal, the soft dorsal will also erect,” he said.

Invasive white perch are spreading through the Arkansas River system, but they have no stripes and Johnston said not to worry about ID on those because they’re so different.

“You’ll know what it is if you catch one of those,” he said.

Good to know there is at least some certainty out there.