Creek Bends: What a burn!

It stinks, but calling the fire department to your prescribed burn can be just what the doctor ordered

It is disconcerting to see a stump shooting flames and debris six feet into the air like a decrepit rocket engine 20 yards outside your chosen burn area.

Communication with your forestry department and fire officials, and, if you’re lucky enough to have one, a prescribed burn association are essential ingredients for any prescribed burn.

But calling them out sirens wailing is way, way down on the list of desirable outcomes.

The history

I’ve covered prescribed burns and the general subject for decades, from Alaska boreal forests to Oklahoma high plains, and I guess I’ve become a disciple of sorts.

Fire is an underappreciated natural part of our landscape that we, for the most part, have failed to appreciate in the design of our homes and managed landscapes. We tend to suppress it until it ultimately explodes in a royal and costly conflagration.

The landowners at Snake Creek have embraced the idea of regular prescribed burns to improve habitat and battle invasive plants. Spring 2022 was the last and first time they burned the creek bottoms.

They set fire to the whole 18 acres. It was a little green, a little late in the spring, the winds were light, and the results were somewhat disappointing.

Last Saturday, I fired up a corner and burned a little less than an acre. It was a well-behaved little burn that removed leaf litter and singed the buckbrush and some green briar in the woods, but it fizzled out when confronted with any log, large stump, or thick tangles. Wind gusts hummed in the treetops, but the fire found little air on the ground.

Again, disappointing.

Things at the base of that north-facing ridge in the creek bottom tend to stay moist. As the sun set, I felt the humidity rise, and the fire fizzled out.

That brings us to Sunday.

The patient

Sunday was a minor burn of a little over 2 acres to complete the swath I started at the base of that 90-foot-high, north-facing ridge on Saturday. Imagine a swath of land shaped like a perfecto cigar, narrow at both ends, a little over 30 yards wide at its widest point, and about 180 yards long.

I’d light the narrow downwind point to the northeast and train it to burn southwest along the base of the ridge and into the wind. Our new bulldozed fire break would keep it in check along the south margin. On the north, I’d patrol our well-worn two-track road for the first 70 yards and a fire break along an old brushed-up fenceline the rest of the way.

In addition to the three or so acres of mixed woods and open grassy meadows at the base of the forested ridge, fire breaks divide the creek bottom into two more east-to-west sections. Across the firebreak to the north is a proper meadow of nearly six acres with some scattered large trees, and across the two-track north of that is about eight acres of riparian zone and Snake Creek.

In addition to those fire breaks, it has Snake Creek as a boundary to the north and a county road to the east. So, under decent conditions with any southerly breeze, a fire ain’t goin’ nowhere we don’t want it to go.

Just one catch, though. An abandoned house full of trash, booked for later fire and demolition, sits near the county road. We’re not ready to burn that yet, so I didn’t want a fire in the meadow or the creek bottom on Sunday.

The condition

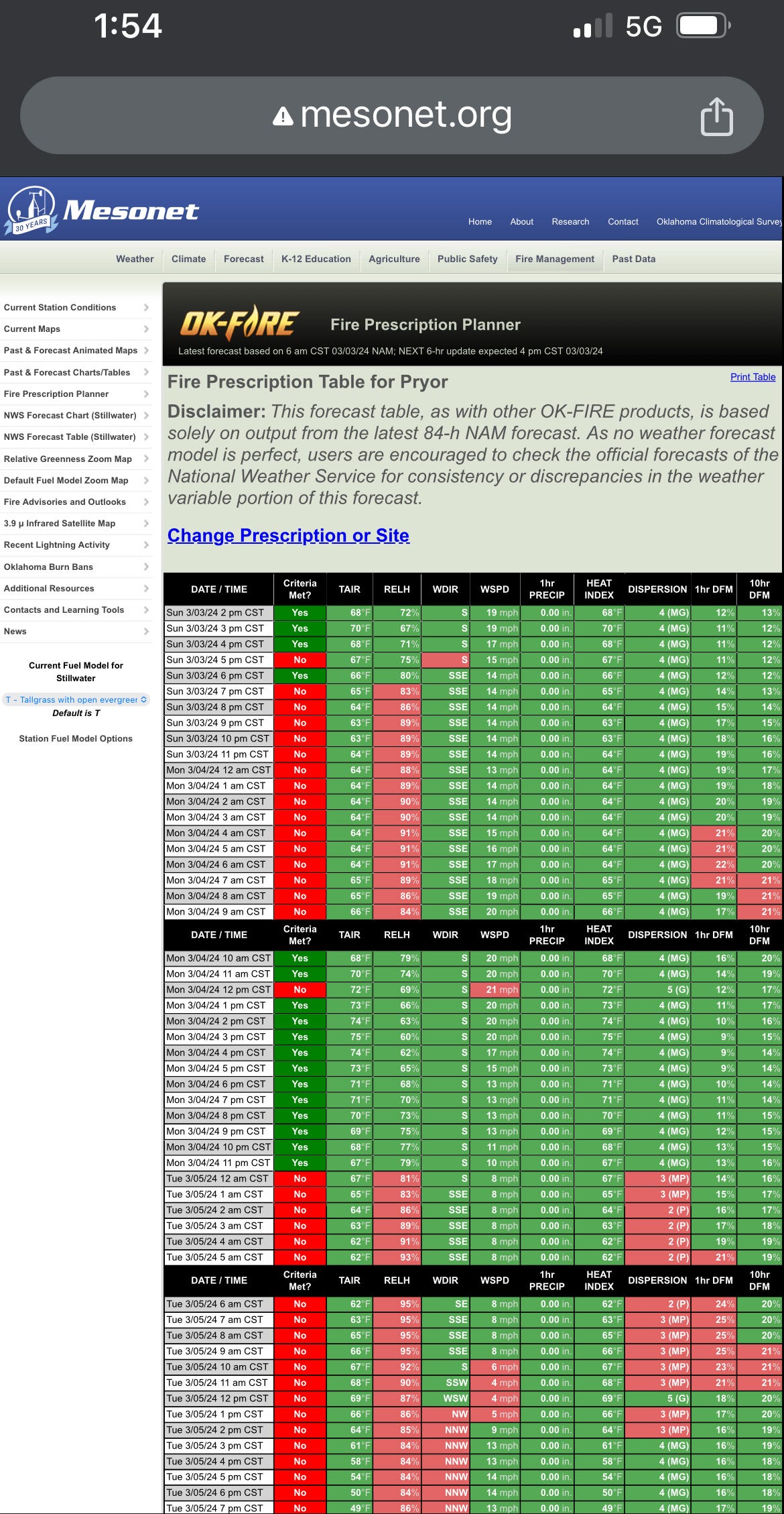

I’ve watched the Mesonet OK-Fire app for months for an opening. For Sunday, similar to Saturday, it listed relative humidity at the high end and winds near the top of our ideal range of 10 to 20 mph.

The burn in 2022 taught us that a stronger south wind is suitable for this relatively damp spot.

The app didn’t show the 30 mph gusts, but the National Weather Service did. Of course, it wasn’t hard to notice when I rolled out of my bunk atop the ridge that morning.

Down below, though, I could hear the gusts on the ridge but scarcely feel them on my face, standing in the middle of my planned burn area.

The app listed 70 to 90 percent relative humidity, and the National Weather Service listed it as 40 to 50. I can’t explain the reason for the difference. Still, either was acceptable.

OK-Fire noted a window with a green light to burn starting at about 2 p.m.

Another factor to check, I learned at a prescribed burning session I covered not long ago, is Dry Fuel Moisture.

According to the Oklahoma Prescribed Burning Handbook, a 1-hour DFM above 10% is recommended for safety, and a 10-hour DFM between 6% and 15% is recommended for a decent burn.

The handbook states that a 10-hour DFM higher than 15% means your fire will likely fizzle “in certain fuel types.” I suppose I found those fuel types on Saturday.

According to the handbook, spot fires are a big concern when that 1-hour DFM drops to around 5%, rare above 11%, and of no concern at 20% or above.

When I called the county fire dispatch center to let them know I planned to burn, I asked about general conditions. The answer was, “We’re not recommending it because we’ve had some get away from people, but we’re not under a ban or anything.”

With the day’s winds, it was not a great day for burning in most places. However, I stood in the middle of the burn area for a while before starting the fire, and it felt safe. The gusts weren’t hitting it.

When I fired up, the relative humidity was 72%, the 1-hour DFM was 12%, and the 10-hour DFM was 13%. The National Weather Service put prevailing winds between 15 and 19 mph from the southeast, with occasional gusts to 30 mph.

Below the ridge, it felt more like a 10-15 mph southwest wind with occasional insignificant gusts.

Yes, southwest, not southeast. I can’t explain it, but that’s how the wind works in that valley. I know from hunting deer below the ridge that the wind swirls—it constantly swirls. This wasn’t the first time I stood there expecting a sustained wind over my left shoulder and felt it hit my left cheek instead.

Regardless, the relative humidity was high, and moisture readings looked safe. My experience on Saturday made me think I had little to worry about in the wooded areas. I even felt a little swirling might help things along.

Diagnosis, overconfidence

The initial burn at that U-shaped southeast tip couldn’t have gone better. As it spread in both directions, I mopped the northeastern edge with a steel bow rake and quickly had a nice wide black swath with the only fire spreading northwest between the two-track and our freshly bulldozed fire break.

Nothing to it.

A few gusts heated things up, and this burn was well on its way and looking good. I kept an eye on anything that might jump the firebreak near the ridge, but it was a mellow fire along that southern edge. It had already skipped around and left some moist areas untouched.

Out at the two-track, I managed it with the steel bow rake. It was so easy to control with a few swipes of the flat side of the rake I even let it creep across the crushed dead grass of the road.

This was going to go quickly and quite well.

A couple of times, the wind pulsed and swirled, the fire surged, and I heard some excellent popping and cracking where the briars were thicker in the center of that swath.

I cheered it on. “There ya go! That’s what we need,” I said to no one but the wind.

I just stood there with the rake in my hand and watched. In the back of the Kawasaki Mule, nearby, I had a round-point shovel, backpack leaf blower, a 5-gallon bucket of water (and a nearby creek), and a cordless power washer. That little cordless washer, I have to say, has been handy in many ways around camp. On the “shower” setting, it is excellent for tending a brush pile or a minor burn in short grass.

I felt over-prepared!

About 70 yards along, I pulled out my camera to take a photo of the fire working beautifully into the wind.

That’s when I saw something orange out of the corner of my eye.

That stump shot fire and debris so high I couldn’t believe it. It was up the two-track, about 20 yards down toward the creek and just below the hill leading up to the old abandoned house.

The treatment

Well-behaved as it was, my fire did need occasional tending to keep it out of the meadow. Running over to check on that stump was risky, but I grabbed the water bucket and bolted.

Looking at it, I thought, “Well, Bonehead, there’s your ‘rare’ spot fire. Now what?”

I can’t run a 40-yard dash over uneven terrain carrying a bucket of water in a few seconds like I could 40 years ago. By the time I surveyed the stump, hit it with the water (to nearly zero effect), and returned, I was winded. I had to hustle to fight the fire back to the two-track while I figured out what to do.

That stump with the flames shooting up in the air had me spooked.

A fire break from two years ago lay between that stump and the old house, but it hadn’t been maintained. The house was still another 50 yards uphill and against the wind to the southeast, but still.

I called the next-door neighbor and asked his thoughts on calling the fire department. He knew the lay of the land. Fire wasn’t readily spreading from the stump in the creek’s damp, wooded area. Still, it was throwing sparks up high, and if that stump was dry enough, other things might be too.

“Yeah, maybe you should call ’em,” our neighbor said.

I called the fire department, left my “good fire,” and went to work with the backpack leaf blower, clearing ground cover downwind of the stump and along that old fire break while I waited to hear the sirens.

Meanwhile, my “good” fire crept across the two-track and started back downwind toward the creek.

In hindsight, I could have stayed up there, tended the two-track, and left that stump for the fire department. It was throwing sparks while I cleared the ground around it, but it didn’t seem to be going anywhere.

Discharged

When those boys in the red trucks showed up, I pointed toward the stump, and they rolled right on past me to the apparent burn along the two-track.

Note: The fire department comes to extinguish all fires, not to help you complete your prescribed burn.

A second truck rolled down the fire break at the base of the ridge to kill the fire on that end. The third truck stopped and pulled a hose over toward the stump.

With multiple fire breaks wide enough for a truck or the easy deployment of a man dragging a hose and the fire’s proximity to the two-track, it took them about 10 minutes, if that, to douse everything.

I chatted with the crew a little, apologized for the callout, and marveled at that danged stump lighting up when, a day earlier, I watched the same “fuel type” extinguish anything that touched it.

“All it takes is one ember,” one said while twirling his finger in a circle.

During one of those windy swirls that I cheered, no doubt, an ember rose to float downwind and find the hollow of that stump. With air entering at the bottom and rolling out the top, it was a chimney awaiting a spark.

As they prepared to leave, they asked if I planned to stay around to mop up. Of course, I’d already planned on that.

The danged stump and a hollowed-out log on the ground that I assume was once its trunk still glowed red and puffed little embers.

One of the guys looked over at it dismissively.

“That ain’t going nowhere,” he said.

I refilled my bucket and drove around, dousing sad little flames with the power washer. At one point, I turned it on the stump and log. It just sizzled and rekindled.

Four hours later, I made a few trips to the creek with the bucket and fully extinguished the log and the stump before I hit the sack.

He was right. That fire around that stump had gone nowhere.

Revised prescription

Any of four easy calls up front would have saved Sunday’s troubles.

I can write 30 mph gusts off the allowable fire conditions. Even if I am in a protected area, the winds at the treetops are not what they are on the ground. Embers rise, and even conditions say spot fires are “rare,” well, rare things happen.

I could have called a buddy. I’d have had no issues if just one other person had been on site. One person would have had ample time to use the leaf blower to clear the ground and ferry over a few buckets from the creek to douse that stump.

I could have taken time over the past weeks to maintain that old fire break. I just had it in my head that we planned to burn those buildings along with that area at some point, so why? Well, if you go to the trouble of creating a fire break, maintain it.

A better water source, like a small pump, tank, and hose, also could have done the trick. I was under-gunned for that flaming stump with the cordless washer, handy as it is. Hauling buckets from the creek worked but was too time-consuming initially. And luckily, this particular spot was only about 15 yards from an easily accessible creekbank.

Even though the fire was within our planned burn area and may have taken a long time to reach that old house, if ever, I made the right immediate move. That stump was not where I felt it was 100 percent safe.

If I ever again think we need help from the fire department, I won’t hesitate. That’s why folks pay those annual dues to the rural fire department and why you call dispatch before you strike a match.

Those boys didn’t seem upset at all about coming out to help. It’s almost like they enjoy blaring sirens and spraying those hoses when nobody’s in danger; they have easy access to the flames, and, in the end, it wasn’t going anywhere.

It is always better to be safe than sorry; you can adjust your prescription and light a match another day.

Good story. Thanks