Count on it, ALT is in your outdoor future

Asian Longhorn Ticks are getting noticed, but they're not new, and they're here to stay

The first story tip I had on Alpha-Gal meat allergy and ticks was nine years ago.

A teenager in Owasso had it, and it took his parents some time to find out why they had to take the kid to the ER on a hot June night in 2015. The condition was so new that the link between it and lone-star ticks was still conjecture, the subject of only one or two ongoing studies.

Now, several friends, and it seems every other friend-of-a-friend has it to some degree. All this didn’t happen suddenly; we just finally figured out what was happening and put a name to it.

So, when USDA and Oklahoma State University Extension issued Ag alerts on Oklahoma’s first documented Asian Longhorned Ticks last month in Mayes County, I wondered how long they’ve been around. Then I called the state’s tick expert and did some digging around here and there over the past few weeks.

To be clear, the main targets of the ALT alerts are cattle ranchers and farmers in eastern Oklahoma. As a smart-aleck and prophetic pretender, I’d say they’ve been around for a while, already are endemic east of I-35, and the next round of headlines will result from some outdoorsy person who is unlucky enough to be the first human to have their illness tracked to one of these little buggers.

That seems to be how things have gone with ticks in recent years. We spot one and find out it causes an illness; before we know it, it’s commonplace.

Also, to be clear, while ALTs may cause heavy infestations in livestock that result in decreased production and growth, abortions, and death and may transmit bovine theileriosis, no people have reported illness in the United States.

However, the USDA reports that “while there have been no reports in the United States, the longhorned tick is known to transmit the agents of certain livestock and human diseases in other countries, including anaplasmosis, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, theileriosis, and rickettsiosis, as well as several viruses.”

Jonathan Cammack, Oklahoma State University Extension assistant professor and OSU Extension specialist with the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, is the state’s lead scientist on ticks.

Cammack agreed the ticks likely are endemic, which simply means they’ve established a population that is here to stay. How widespread they are is hard to say, but consider the following.

The ticks, native to eastern Asia and southeastern Russia, were first documented on sheep in New Jersey in 2017. But that news led to a re-examination of ticks found in 2010 on white-tailed deer in West Virginia. They went undetected in the eastern region for at least seven years.

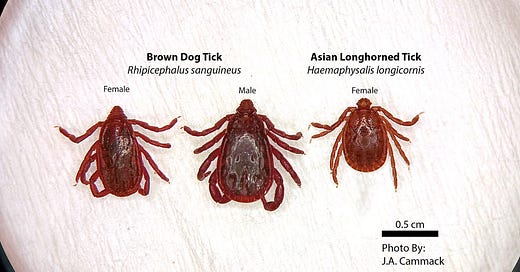

They are smaller than other ticks and hard to distinguish from common species typically dismissed as “seed ticks.” Most often, they would appear as a tick about the size of a sesame seed. The females, when swollen, are about the size of a pea and greenish, as opposed to the brown/beige hue of a swollen dog tick or lone star female. So, there’s one ID tip. Other than that. Carry a magnifying glass.

They’ve been documented to use at least 150 hosts (cattle to humans to mice and birds). Males are relatively rare, and females are truly parthenogenic (the Greek term for “virgin birth”), meaning they can lay their 2,000 eggs, and they will be viable without the need to mate.

They are hard to identify, tiny, can attach to warm-blooded animals large, small, furred, or feathered, and can reproduce without a mate whenever conditions are right.

Cammack agreed that it is a recipe that indicates they likely have been here, especially with documented finds in Missouri and Arkansas in recent years. Now that people know to look for them, we’ll find more. I’m guessing a lot more when conditions are right.

“I think if we’ve learned anything from how they’ve been moving across the country the past 10 to 15 years, it is that they are here to stay, and we just have one more species on our list to be on the lookout for when we are checking animals for these pests,” Cammack said.

Relatively moist conditions this summer have been prime for ticks. What we most often recognize as “seed ticks” are likely nymphal lone star ticks, Cammack said. Now, we can add Asian longhorned ticks to that list.

“Lone star tick numbers have been incredible this summer,” Cammack said.

Lone star ticks are notorious for coordinating their nymphal “seed tick” stage and climbing to the tips of grasses in a small area. Dozens might latch onto a host who is unlucky enough to brush past a tiny, grassy area overloaded with ticks.

Even with permethrin and DEET treatments, picking a seed tick or two off my clothing is not unusual. They don’t survive long in those treated threads, but if I see them, they’re off!

I’m curious enough now to want to look closer at them, mainly because I spend so much time outdoors in eastern Oklahoma. I almost want to find some.

Almost.

Oklahoma is at the far western edge of their expansion, and folks out west likely have little to worry about. Cammack chose I-35 as a convenient dividing line that defines “somewhere in the middle of the state” as the extent of their western expansion.

“They rely on moist layers near the ground to reproduce,” he said. “Anything farther to the west than that, the soil will likely be too dry. There will likely not be enough rainfall or enough humidity in the environment to sustain the population.”

Cammack said the only ID tip he can offer, other than the shape and color of an engorged female per the USDA, is that these “seed ticks” are rounded where others are more oblong.

For example, an Asian longhorned tick might be of only slightly less width than a dog tick, but the dog tick will be longer, he said. Either might be in the same brown to reddish-brown color range.

I will jump out on a limb and assume OSU doesn’t want a hundred baggies of seed ticks added to its collection by hunters and hikers this fall. Still, the university does ask that if you suspect animals or livestock are infested with Asian longhorned ticks, you contact your veterinarian and/or county extension office.

Specimens can be collected (invest in a quality pair of those super-pointy tweezers, and you’ll thank me) and placed, dry, in a sealed container such as a Ziplock sandwich bag. A small water bottle or glass vial containing 70% ethanol also can be used.

Bags can be mailed to the Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory using the General Submittal Form at this link. Include a piece of paper that notes “Asian longhorned tick ID,” and include the address of where it was found, the date collected, and the host the tick was collected from. Send those to Oklahoma Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, 1950 Farm Road, Stillwater, OK 74078

I may never go outside again! LOL